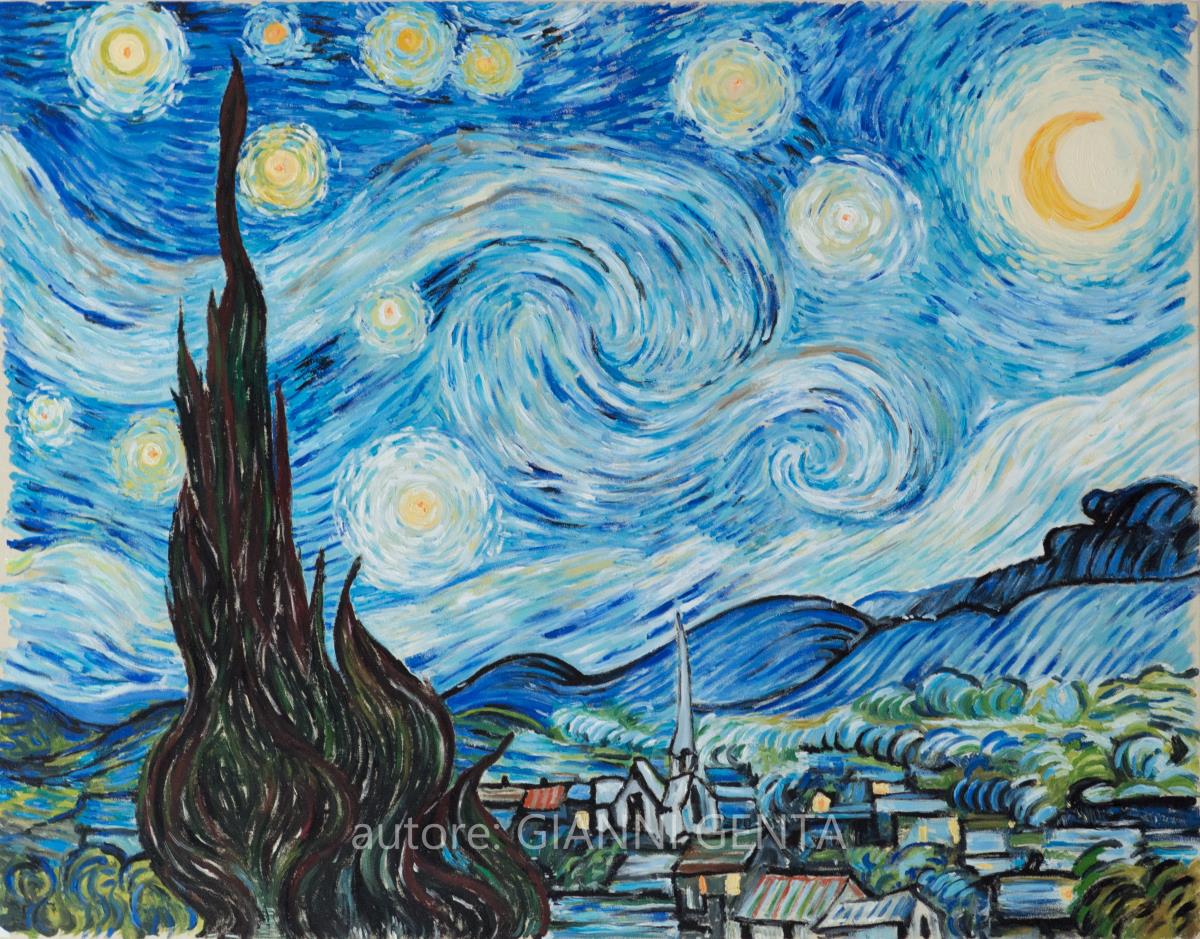

Potato Eaters

of Vincent Van Gogh

Potato eaters (De Aardappeleters) is a painting by Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, made in 1885 and preserved at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Potato eaters propose an authentic and unmodified representation of reality, where subjects generally considered to be unworthy of pictorial representation, such as Nuenen peasants, are not discriminated against by their “ugliness” but, indeed, are presented with a sincere style and without any aesthetic pleasures. Van Gogh, then, brings realism to the extreme consequences: if painters such as Millet and Jozef Israëls conferred on their peoples a strong emotional and sentimental value, in this work van Gogh takes distances from the romantic idyll that sparked in the works of his illustrious predecessors, and comes to an interpretation of the raw social, impetuous, exquisitely realistic and exasperated social data, to culminate in the expressive enhancement of the somatic features of the five diners.

The work, in fact, depicts the interior of a poor home of Nuenen, just lighted by a dim light that, gushing from the oil lamp hanging on one of the beams of a ceiling, languishes with its dazzling glare on the white headphones, on cups of coffee, and on the thin meal of the five diners. At the heart of the composition, in fact, we find a family of peasants who, after spending the day grabbing lands and sweating in the fields, gathered around a pie to eat dinner. An elderly lady, curled up by the fatigue accumulated during the day just finished, pours black coffee and boiling in the cups, while what her husband is likely to have is tapping the appetite from the potato in her hand. A woman on the left, with the beauty now finally cracked, ventures with the fork on the tray with boiled potatoes, still warm and smoky. The woman’s gaze is tenderly aimed at the man she has next to, whose features are severely abbrutured by fatigue and resignation for a destiny that will never change. In the foreground, finally, we find a little girl: we can not see what he is doing, although we can well imagine that his hands are in his chest and that he is praying before the meal (it would seem, then, that hiding the face of the girl Vincent he wanted to “save it” for pictorial ways from the miserable fate that opens in front of him.) [8] The looks of the various peasants are elusive, they do not cross, and above all, the little girl in the foreground reinforces the idea that the observer of the painting is improvising in such an intimate moment, acting with his side as a real factor of spacing. The presence of this little girl is also very interesting not only because it tries to overcome the maladies radial arrangement of the family, joining the two parts in a sense, but also because positioning in the intermediate position between the observer and the light source gives life to a fascinating backlighting effect.

The same Van Gogh points out how the gnarled hands that are now grasping the potatoes are the same ones that, during the day just spent, have sown, grown, and collected:

“I wanted, working, to make it clear that these poor people, who in the light of a lamp eat potatoes using the dish with their hands, has seized the very land where those potatoes grew; the picture therefore evokes manual work and makes it clear that those peasants have honestly deserved to eat what they eat. I would not want everyone to just find it beautiful or valuable ”

(Vincent van Gogh [8])

The same theme as interpreted by Jozef Israëls

The miserable peasant farms are all around, where there is a rudimentary clock (in the upper left corner), a teapot (in the diametrically opposite corner), the various cutlery in a wooden bowl and, above all, the printing of a Crucifix. This is a little detail: van Gogh, in this way, reiterates the intimate sacredness of the evening meal, a rite that is deeply rooted in the human conscience and which refers to primal values, such as the ethos of labor, the importance of the family, the qualities of simple things, but made with the heart, and therefore true. [9] Van Gogh himself, intruding into this archaic and ancestral world, returns artistic dignity at this moment more than sacred, where the various villagers set their burden of daily struggles and finally find a moment of union and solidarity. It would seem almost a ceremony with a precise code of clothing (men wearing the cap, women’s headset) and with a silent gratitude that lurks on the various figures, which – with slow gestures, but thoughtful looks and glances so marked, but satisfied –

This post is also available in:

Italiano

Italiano